|

| Photo courtesy of Todd Bainbridge

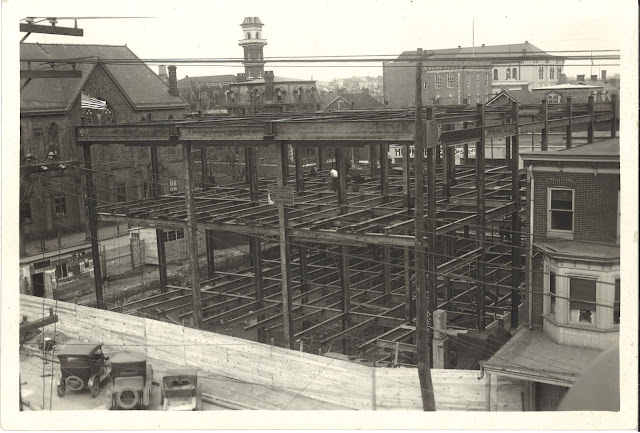

Do you recognize this building being built? It only took me about 30 seconds.

|

As a history buff, I often find myself looking backward for clarity and similarities during times of extreme change in this country.

History can also be a source of comfort by reminding us that things have been this bad before, and we survived.

Trying to get a handle on impeachment? Look at what happened last time we went through this.

What are the consequences of the concentration of extreme wealth? Read up on "the gilded age."

So there was a certain amount of synchronicity at work this week, during a time of extreme upheaval in the local news landscape, that brought Todd Bainbridge's photo to one of my favorite non-political Facebook pages.

There, on "Good Old Days of Pottstown," where folks mostly post old photos and "does anyone remember?" questions, was a photo of steel framework of a building being erected in 1925.

Recognizing the since-shortened watchtower at the Phillies Fire Company, where wet hoses were hung to dry; and the Trinity Reformed United Church of Christ I walked past for more than 20 years on the way to work, I realized it was The Mercury building at High and Hanover streets being constructed.

|

| The Mercury building as it appears today. |

That's when William Heister and the paper's legendary first editor, Shandy Hill, moved the paper they had founded six years earlier, into the building.

But for all intents and purposes, everyone knows it as The Mercury building.

The sign remains on the corner one year after I wrote the obituary for news operations there.

In it's first issue, Hill wrote The Mercury would be “frank and fearless in all matters, especially in which Pottstown has a vital interest.”

In terms of the mission of local news, that remains as true today as it was in 1931. What is not the same, is our ability to continue to do so.

What's happened?

Margaret Sullivan, the media columnist for The Washington Post provided probably the most succinct round-up of last week's local news shockwaves:

Gannett and GateHouse, two major newspaper chains, finished their planned merger, and the combined company intends to cut the combined budget by at least $300 million. That will come on top of unending job losses over the past decade in the affected newsrooms of more than 500 papers.Regular readers of this blog know that Alden also owns, and has gutted not only The Mercury, but the other papers it owns in its "Philadelphia Cluster" -- The Times-Herald in Norristown, The Daily

The McClatchy newspaper group — parent of the Herald and Charlotte Observer — is so weighed down by debt and pension obligations that analysts think it is teetering on bankruptcy.

And the storied Chicago Tribune on Tuesday fell under the influence of Alden Global Capital, a hedge fund that has strip-mined the other important papers it owns, including the Denver Post and the Mercury News in San Jose.

|

| Space for rent in The Reading Eagle building. |

In addition to the relentless drumbeat of staff cuts, the most visible example of the strip-mining of local newspaper assets is off-loading the real estate.

In addition to selling The Mercury building, Alden has also sold or is actively marketing the Norristown, West Chester and Delaware County buildings and recently announced on The Reading Eagle's front page that there is "space for rent" inside.

Because irony never takes a holiday, I hasten to point out that this same cluster of papers provided Alden Global Capital, and its top man Heath Freeman, with a $18 million profit in 2017, as reported last May by the undisputed chronicler of these sad times, Ken Doctor and his Newsenomics column in Harvard University's Neiman Foundation for Journalism.

|

| SOURCE: Ken Doctor |

"DFM reported a 17 percent operating margin — well above those of its peers — in its 2017 fiscal year, along with profits of almost $160 million. That’s the fruit of the repeated cutbacks," Doctor wrote, noting that none of that profit, none of it, was reinvested in the business.

Instead it was spirited away to invest in controlling stakes of distressed companies like Fred's Pharamacy and Payless Shoes, both of which almost immediately dove into bankruptcy under the leaden management of Alden and the "management" fees it extracts.

In the combined Fred’s and Payless store closures this year, roughly 22,000 people have lost their jobs.

Some of those workers stood with News Guild investigative reporter Julie Reynolds and myself in Washington, D.C. this summer when several Congress people and senators (and presidential candidates) announced a bill to try to regulate the wanton greed of hedge funds and private equity.

Alden's business practices are so shady, it is under investigation by the U.S. Labor Department for using employee pension funds as a piggy bank to prop up its bad investments.

And, as Reynolds reported last month, "A federal bankruptcy

judge on Oct. 16 ordered Alden to turn over requested documents to (Fred's Pharmacy) creditors and will allow them to question Alden president Heath Freeman under oath."

The creditors have claimed Alden's purchase of Fred's was "shrouded in suspicion" and the creditors told the court that Alden “funneled $158 million from a floundering newspaper business in order to purchase (Fred’s) stock—stock which has since that time lost 97% of its value.”

All of this to say that the employees of Tribune newspapers -- which include The Morning Call in Allentown, and the Chicago Tribune, The Baltimore Sun, The Hartford Courant, the New York Daily News and The Virginian-Pilot -- are truly anxious about Alden's majority shares in Tribune.

"We're deeply concerned that Alden Global Capital has purchased a majority share in Tribune Publishing. Alden has hurt journalism and journalists," The Chicago Tribune Guild Tweeted as soon as the news of the sale of stocks to Alden made headlines.

Alden's business practices are so shady, it is under investigation by the U.S. Labor Department for using employee pension funds as a piggy bank to prop up its bad investments.

And, as Reynolds reported last month, "A federal bankruptcy

|

| Heath Freeman |

The creditors have claimed Alden's purchase of Fred's was "shrouded in suspicion" and the creditors told the court that Alden “funneled $158 million from a floundering newspaper business in order to purchase (Fred’s) stock—stock which has since that time lost 97% of its value.”

All of this to say that the employees of Tribune newspapers -- which include The Morning Call in Allentown, and the Chicago Tribune, The Baltimore Sun, The Hartford Courant, the New York Daily News and The Virginian-Pilot -- are truly anxious about Alden's majority shares in Tribune.

"We're deeply concerned that Alden Global Capital has purchased a majority share in Tribune Publishing. Alden has hurt journalism and journalists," The Chicago Tribune Guild Tweeted as soon as the news of the sale of stocks to Alden made headlines.

The guilds of all Tribune's newspapers, including The Morning Call, immediately issued (and Tweeted) a statement that read, in part:

Alden is not a company that invests in newspapers so they succeed. They buy into newspaper businesses with the express purpose of harvesting out huge profits -- well above industry standards -- and slashing staff and burning resources.

We know we are looking at the real threat that Alden is looking to bleed its next chain of newspapers dry.Adding insult to injury, Tribune announced just prior to the Alden stock purchase that it would issue a quarterly dividend to stockholders next month worth $36 million "despite the company being in the red by $9.1 million for the first three quarters of 2019," according to Doctor.

All this while telling the News Guild negotiators at the bargaining table for Chicago, Virginia, Hartford and Allentown that there is no money for raises and they have to eat a 6.4 percent hike in their health care costs.

Added to this Alden-apocalypse is the Gannett-Gatehouse merger which is also financed by private equity hedge funds, Fortress Investments and Apollo Global Management, which will harvest a whopping 11.5 percent interest rate on its loan, requiring savings of $400 million to make the payments.

|

| Image filched from Ken Doctor's column |

And at McClatchy, now the nation's second largest newspaper chain, a Bloomberg News headline indicating the company may be near bankruptcy due to its efforts to get out of its pension fund obligations, sent the company's shares tumbling 82 percent on the market across five trading days, according to Doctor.

With $700 million in debt, down from the $5 billion it took on in 2006 when it acquired Knight-Ridder, former owner of The Philadelphia Inquirer, McClatchy owns 29 newspapers with a combined circulation of three million, including The Kansas City Star, The Miami Herald, The Charlotte Observer, The Sacramento Bee (California), and the Star-Telegram (Fort Worth, Texas).

If McClatchy gets reorganized through bankruptcy, another hedge fund, Chatham Asset Management, "the company’s biggest lender and shareholder, is in the driver’s seat," wrote Doctor.

And, Doctor is reporting there are rumors of a merger between Tribune and McClatchy which would once again put money in Alden's pocket. Similarly, Alden tried to scotch the Gannett-Gatehouse merger by making its own bid. When that failed, it bought stock in Gannett and supported the sale.

As Doctor wrote in his Nov. 20 analysis: "The impact is obvious. As America has moved from jokey indulgences in truthiness to a point where fact fights for its very life, it’s the bankers who are deciding what will be defined as news, and who and how many will people will be employed to report it."

Which is where I return to my refuge in history which, in this case, provides more warning than comfort.

We must use our time machine to go back to Medieval times to find the example of life without a free press. To be allowed to publish in Elizabethan England, for example, one needed to be in a guild (no relations to today's union other than the work done by both) which had permission from the crown.

And if you published without permission, or something the crown did not like, you were punished, sometimes with jail.

You suffered worse during the religious wars in Europe if, for example, you were in possession of a protestant Bible in a Catholic nation, or a Catholic Bible in a protestant one.

What were Martin Luther's 95 theses about the church other than an early example of the free press, the free expression of ideas presented to as broad an audience as possible?

There is no better indication of the importance of the role played by a free press in this country's founding than its presence in the very first of the Amendments made to the Constitution.

And while the First Amendments means the government can make no law abridging the freedom of the press, it is silent on whether the press can be abridged by other increasingly powereful interests in our society, like Wall Street's single-minded pursuit of profit over purpose.

That is the danger posed by monied ownership of newspapers and, perhaps, by the death of the traditional, long-standing but crumbling model of local news ownership.

As I said at that Washington news conference this summer:

It's about more than my job, and the jobs of journalists across the country. It's the function those jobs perform that matters.

I've lost track of the number of studies I've referenced that show people's taxes go up without a local news source, largely because those same Wall Street firms that are breaking the back of newspapers to make more money, charge higher interest rates on bonds taken out by local governments that are not curbed by the watchdog oversight of a local news source.

Pretty nice deal. Wall Street makes more money on both ends of that equation. Yay vulture capitalism.

Other studies show without local people become less engaged in their communities, more polarized, vote less and fewer people run for office.

Thankfully Joshua Benton did it for me when he wrote the following in April for Neiman Lab:

"With fewer resources, though, reporters are more likely to report on an issue only when it reaches a public state of prominence — by which time the city’s plans may have already been shaped without much public input," Benton wrote Friday, undermining the "early warning system" that more robust local news coverage traditionally provided.

What does the threat of losing local news mean?

Which is where I return to my refuge in history which, in this case, provides more warning than comfort.

We must use our time machine to go back to Medieval times to find the example of life without a free press. To be allowed to publish in Elizabethan England, for example, one needed to be in a guild (no relations to today's union other than the work done by both) which had permission from the crown.

And if you published without permission, or something the crown did not like, you were punished, sometimes with jail.

|

| Martin Luther's 95 theses, a free press in action. |

You suffered worse during the religious wars in Europe if, for example, you were in possession of a protestant Bible in a Catholic nation, or a Catholic Bible in a protestant one.

What were Martin Luther's 95 theses about the church other than an early example of the free press, the free expression of ideas presented to as broad an audience as possible?

There is no better indication of the importance of the role played by a free press in this country's founding than its presence in the very first of the Amendments made to the Constitution.

And while the First Amendments means the government can make no law abridging the freedom of the press, it is silent on whether the press can be abridged by other increasingly powereful interests in our society, like Wall Street's single-minded pursuit of profit over purpose.

That is the danger posed by monied ownership of newspapers and, perhaps, by the death of the traditional, long-standing but crumbling model of local news ownership.

As I said at that Washington news conference this summer:

"Wall Street exists to pursue profit. That’s its purpose.

But maybe it’s time to recognize that some institutions in America are more important than profit; that these institutions should be in the hands of those dedicated to their preservation, not to those who willfully plunder them for a 16th mansion in Miami Beach or to put another addition to their Montauk beach house."

|

| Yours truly speaks truth to power in Washington. |

I've lost track of the number of studies I've referenced that show people's taxes go up without a local news source, largely because those same Wall Street firms that are breaking the back of newspapers to make more money, charge higher interest rates on bonds taken out by local governments that are not curbed by the watchdog oversight of a local news source.

Pretty nice deal. Wall Street makes more money on both ends of that equation. Yay vulture capitalism.

Other studies show without local people become less engaged in their communities, more polarized, vote less and fewer people run for office.

Thankfully Joshua Benton did it for me when he wrote the following in April for Neiman Lab:

What do strong local newspapers do? Well, past research has shown they increase voter turnout, reduce government corruption, make cities financially healthier, make citizens more knowledgable about politics and more likely to engage with local government, force local TV to raise its game, encourage split-ticket (and thus less uniformly partisan) voting, make elected officials more responsive and efficient, and bake the most delicious apple pies. Okay, not that last one.

Local newspapers are basically little machines that spit out healthier democracies. And the best part is that you get to reap the benefits of all those positive outcomes even if you don’t read them yourself. (On behalf of newspaper readers everywhere: You’re welcome.)Without local news, or with newspapers that are a shadow of their former healthy selves, a gap opens.

"With fewer resources, though, reporters are more likely to report on an issue only when it reaches a public state of prominence — by which time the city’s plans may have already been shaped without much public input," Benton wrote Friday, undermining the "early warning system" that more robust local news coverage traditionally provided.

"As newspapers cut back on coverage — just as when they cut back on distribution — the first things to go are the farthest away from headquarters," he wrote.

Look no further than the Mercury for an example of that. I can't remember the last time I was able to get to a meeting of the Upper Perkiomen School Board, North Coventry Supervisors or Trappe Borough Council.

With meetings occurring the same night, I have to make my best guess and as a result, I miss things.

For a perfect example, look no further than the Phoenixville School Board.

Attending Thursday's public hearing on the purchase of a 30-acre East Pikeland property for a new school, I suddenly became aware that Superintendent Alan Fegley had a new four-year contract.

More significantly, I checked the minutes of previous meetings and was dismayed to discover it was adopted in September, several months before the current contract expires and ahead of the installation of a new majority on the incoming school board.

Phoenixville readers got no early warning from The Mercury on that development, despite the fact that it played out over several meetings and happened at about the same time an investigation into the mishandling of funds by the district's chief financial officer had begun.

Fake local news?

Sometimes, citizens fill that gap left by the loss of local news with more national news which is becoming more partisan and more fractious.

Many local journalists then find themselves painted with the same brush.

Many local journalists then find themselves painted with the same brush.

As Benson wrote: "as media consumption becomes more nationalized, the yelling and spinning on cable news colors how people think about their hometown daily."

One reporter was quoted in the report as follows:

Uncharacteristically, I will end this screed on a positive note.

There are success stories out there.

They have visited and profiled operations in Mississippi, Maine, Massachusetts, southern California and the Bay Area and Houston.

They have visited and profiled operations in Mississippi, Maine, Massachusetts, southern California and the Bay Area and Houston.

What I found most interesting about it is its "subscription-and-micropayments business model. As you’ll see if you register (for free) on the paper’s site, NewsAtomic, after an introductory-offer period, articles from the paper for non-subscribers cost 25 cents apiece."

The paper is also recruiting future readers, and training future journalists, by partnering with the local high school newspaper.

“We started to look at what was converting people who just visited the page to people who wanted to pay us,” Jay Senter who founded the site with his wife Julia Westhoff, told Schmidt.

“The accountability journalism, the Civics 101 content we put out there — that was the kind of stuff that seemed to get people over the hump and giving us money every month…Things that were on the fires-and-car-accident side of things would get a lot of pageviews, but didn’t seem to have lasting impact on the way that people live their lives around here.”

It keeps the site accountable, and owned, by the community it serves.

The Salt Lake City Tribune, is the second to do it on a larger scale, having obtained non-profit status from the Internal Revenue Service.

Closer to home, our own Philadelphia Inquirer/Daily News operation went non-profit in 2016 under the Lenfest Institute for Journalism.

But it is not a panacea.

As Schmidt wrote in April, "unresolved financial issues, a new round of buyouts, less-than-stellar staff morale, and a leadership vision some consider hazy on specifics remind the Inquirer that it’s not safe yet."

As negotiations with the News Guild of Greater Philadelphia, of which I am a proud member, continue, the Twitter account there notes workers have gone more than 3,700 days without a raise.

On a smaller scale, Schmidt writes in a Nov. 20 article for Neiman, "alt weeklies," those often free publications you see in honor boxes in most major cities, are experimenting with this approach.

Last week a new report was issued (I told you it was a crazy busy week in local news) by PEN America, a non-profit founded in 1922 by such luminaries as Willa Cather, Eugene O’Neill, Robert Frost and others "to ensure that people everywhere have the freedom to create literature, to convey information and ideas, to express their views, and to access the views, ideas, and literatures of others."

Titled "Losing the News," it covers all the concerns mentioned above, what one local official once described to me as "worshiping the problem," but also highlights some success stories includes some potential solutions.

Among the recommendations are:

News organizations should:

One reporter said these resident attitudes were further tainted by negative attitudes about national mainstream media outlets. “You know, we’re not CNN; we’re not Fox News; we’re not MSNBC…we’re your neighbors. We want to do good by you, but we can’t do that if you hate us or you think that we’re out to get you or you think that we’re out there with an agenda. We’re not and I don’t — sometimes I just don’t know how to get that across to people who vehemently believe otherwise.”

Look no further than The Mercury's Facebook page to see claims of "fake news" being thrown at stories and opinion columns with which some readers take issue.

And sometimes, the gap is filled with actual fake news, and I'm not talking about actual news that Donald Trump doesn't like.

On Tuesday, The Guardian newspaper, which has an online U.S. edition, published a troubling story about "Locality Labs, a shadowy, controversial company that purports to be a local news organization, but is facing increasing criticism as being part of a nationwide rightwing lobbying effort masquerading as journalism."

It offered the example of an Illinois school referendum into which a Locality Labs inserted itself.

Hinsdale School News, a print newspaper that was distributed around Hinsdale voters. The paper had the Hinsdale high school district logo, and the look of a journalistic organization. But, as the Hinsdalean reported, the “newspaper” was stuffed full of articles, mostly byline-free, which had a distinct anti-referendum skew.

“The depths of what they went to were pretty egregious,” said Joan Brandeis, who was part of the Vote Yes Campaign.

“This was purposely done to mislead people into thinking that was a publication from the district.”Apparently, it's not the first time. Here is the gist of the scheme as reported by Adam Gabbat:

Locality Labs operates scores of sites across Illinois, Michigan, Maryland and Wisconsin, often sharing content. In Michigan alone, the Lansing State Journal reported, almost 40 sites opened in one fell swoop this fall.

“It is always a bit troubling in the current environment when websites don’t really indicate what they’re all about, and sort of hide who is behind them, and I think that’s clearly the case here,” said Matt Gertz, a senior fellow at the not-for-profit press watchdog Media Matters.

“In the fractured media environment that we’re operating in now, if you’re just scrolling through your Facebook feed or your Twitter feed and you see an article, you click on it and you might take in the information from there without really ever wondering what the source actually is.”

The CEO of Locality Labs is Brian Timpone, an ex-journalist with a track record of operating dubious news organizations. Timpone’s predecessor to Locality Labs was a company called Journatic, which saw a licensing contract with the Chicago Tribune torn up after it published plagiarized articles and made up quotes and fake names for its writers. Locality Labs did not respond to a request for comment.

Locality Labs’ sites are almost identical in layout. The Great Lakes Wire is similar to the Ann Arbor Times, which bears a striking resemblance to the DuPage Policy Journal and the Prairie State Wire.There's more:

What the sites all have in common is praising Republican politicians, and denigrating Democratic ones.

Last week Illinois sites – including the West Cook News, Grundy Reporter, South Central Reporter and Illinois Valley Times – each ran a story about a thinktank criticizing JB Pritzker, the state’s Democratic governor.

The stories were all written by Glenn Minnis – whose byline was also listed in the Hinsdale School News. None of the articles mentioned that the thinktank in question was a rightwing, anti-tax lobbying organization.And the kicker that makes this all relevant to this column:

Opinion as news is nothing new. But the appearance of the rightwing-skewed Locality Labs sites, presented as merely local news, has been aided by the demise of the local news industry in America as real local newspapers have shut down in droves, sometimes leading to “news deserts.”

About 1,800 newspapers closed between 2004 and 2018, while a University of North Carolina study last year found that 1,300 US communities have completely lost news coverage.

... Gertz said people still tend to have more faith in local news than in national outlets.

“And so there’s an idea here that you can move in and take advantage of that, of both the lack of local news options and the fact that people are inclined to trust local news by creating these hyperlocal news sites and provide no little bit of conservative propaganda.”As Doctor warned us, “the old world is over, and the new one — one of ghost newspapers, news deserts, and underinformed communities — is headed straight for us.”

What can be done?

|

Photo shamelessly stolen from The Colorado Independent.

|

There are success stories out there.

- In Denver, some who left, voluntarily and otherwise, the Alden-owned Denver Post started an alternative local news site called The Colorado Sun.

It is now in its second year and attracting more readers.

- Also in Denver, "where two major papers once thrived, a host of locally run, community-focused outlets are proliferating. One such outlet, Chalkbeat, is reporting from public schools and school board meetings, covering education, one of the biggest casualties of the attrition in local news—and successfully scaling to other states. Nationwide, over 6,500 philanthropic foundations, as well as tech giants, are now financing media initiatives," wrote Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Ayad Akhtar.

- James Fallows of The Atlantic and his wife Deborah has been touring the nation finding all sorts of examples of small-scale local news operations that are sustainable.

They have visited and profiled operations in Mississippi, Maine, Massachusetts, southern California and the Bay Area and Houston.

They have visited and profiled operations in Mississippi, Maine, Massachusetts, southern California and the Bay Area and Houston.

In his latest installment, on Oct. 27, visiting the Shawangunk Journal in New York's Hudson Valley, Fallows wrote:

A theme that runs through nearly all of these reports is the importance of ownership structure.

Times are tough for little newspapers everywhere, but the papers least likely to survive are those that have fallen under the control of hedge-fund and private-equity chains, which are starving them into short-term profitability and longer-term demise. The successful counterexamples are mainly family-owned, community-owned, or in some other way bolstered against the pressure to cut the publication into insignificance.Founded in 2006, The Shawangunk Journal is a print publication, now with a paid circulation of about 2,000.

What I found most interesting about it is its "subscription-and-micropayments business model. As you’ll see if you register (for free) on the paper’s site, NewsAtomic, after an introductory-offer period, articles from the paper for non-subscribers cost 25 cents apiece."

The paper is also recruiting future readers, and training future journalists, by partnering with the local high school newspaper.

- On Nov. 18, Christine Schmidt profiled the northeast Kansas-based Shawnee Mission Post for Neiman Lab and found that the thing everyone loves to complain about, paywalls, are making that site sustainable.

“We started to look at what was converting people who just visited the page to people who wanted to pay us,” Jay Senter who founded the site with his wife Julia Westhoff, told Schmidt.

“The accountability journalism, the Civics 101 content we put out there — that was the kind of stuff that seemed to get people over the hump and giving us money every month…Things that were on the fires-and-car-accident side of things would get a lot of pageviews, but didn’t seem to have lasting impact on the way that people live their lives around here.”

- Or you can try the non-profit model.

|

| Salt Lake Tribune building. |

The Salt Lake City Tribune, is the second to do it on a larger scale, having obtained non-profit status from the Internal Revenue Service.

Closer to home, our own Philadelphia Inquirer/Daily News operation went non-profit in 2016 under the Lenfest Institute for Journalism.

But it is not a panacea.

As Schmidt wrote in April, "unresolved financial issues, a new round of buyouts, less-than-stellar staff morale, and a leadership vision some consider hazy on specifics remind the Inquirer that it’s not safe yet."

As negotiations with the News Guild of Greater Philadelphia, of which I am a proud member, continue, the Twitter account there notes workers have gone more than 3,700 days without a raise.

On a smaller scale, Schmidt writes in a Nov. 20 article for Neiman, "alt weeklies," those often free publications you see in honor boxes in most major cities, are experimenting with this approach.

Last week a new report was issued (I told you it was a crazy busy week in local news) by PEN America, a non-profit founded in 1922 by such luminaries as Willa Cather, Eugene O’Neill, Robert Frost and others "to ensure that people everywhere have the freedom to create literature, to convey information and ideas, to express their views, and to access the views, ideas, and literatures of others."

Titled "Losing the News," it covers all the concerns mentioned above, what one local official once described to me as "worshiping the problem," but also highlights some success stories includes some potential solutions.

Among the recommendations are:

- Collaborating with other local news sources on broader, enterprise coverage of major issues:

- "Investment in revenue-generating staff, such as subscription, membership, sponsorship, and development teams."

- Build diversified revenue streams, including subscriptions, membership, events, sponsorships, and other channels to lessen reliance on grant funding.

- Implement and defend safeguards to ensure editorial independence from funders, adapting existing newsroom traditions, norms, and rules and enacting news ones for noncommercial models.

- Invest in systems and hiring in the areas of nonprofit management and revenue development, including teams to seek, manage, and report on grant funding

- Commit greater resources to preserving public service journalism that is local, rather than national, and that meets the critical information needs of communities

- Negotiate with news outlets to develop new, robust, equitable licensing and ad-revenue-sharing agreements. These agreements should incorporate the explicit aim of supporting the financial viability of local news outlets that produce online content. Negotiations for such agreements must include substantive participation from news outlets—including small and midsize ones and those that serve under-represented communities.

- Restore pre-2017 regulations governing the ownership of TV stations, radio stations, and newspapers to prevent further consolidation and homogenization in local news media.

- Explore legislation and policy to reduce roadblocks for media outlets aiming to innovate or adapt to new market realities.

- Recognize the civic and democratic necessity of strong local news ecosystems and approach the industry as a “public good” rather than a “market good.”

- Increase financial support for local news to approach the levels of support in other democratic, high-income countries

News consumers should:

- Subscribe to and join membership programs for local news outlets.

- Donate to local news outlets (such as public media and nonprofit outlets).

- Speak or write to elected and appointed officials about the importance of local news and the need for more public funding and send comments to the FCC about their deregulation efforts.

- Inform news outlets of local stories that need to be told.

Because if we don't, as a nation, we're history.